Suddenly remembering what you worked so hard to forget

Five years of COVID and a flare-up of multiple sclerosis arrived in a tidy, unwelcome package.

Yes, it was just last month that I wrote about my latest trip to the neurologist and my annual multiple sclerosis checkup.

All was well, as it generally has been for quite some time.

And then a couple weeks later I felt something both distant and familiar: a recurrence of symptoms that could only be described as a relapse, my first in 11 years since being diagnosed.

The spasms in my abdominal muscles wouldn’t go away. There was a weird pain in my neck and uncomfortable tightness in the surrounding muscles. The tension strained my eyes, making me sensitive to light. Fatigue was plentiful. Brain fog was present.

Ugh.

A more superstitious person, the type of person I used to be, would probably say I jinxed myself. But the reality is that I was likely just due.

Even so, there was denial. I messaged my doctor during the onset, when my symptoms were lighter, suggesting hopefully that I might just be stressed out and tired. He put me on a low dose of anti-inflammatory steroids, which seemed to help for a couple days.

But the night before that prescription was going to run out, I had to send another message: Nope, it’s getting worse. This feels like an actual relapse, not just a day or two of random symptoms. Time to bring in the big guns.

So on Wednesday, I started a massive dose of steroids, the general method for calming down the inflammation that tends to drive symptoms of MS. The steroids also hopefully shorten the length of the relapse.

Three days, 1,250 milligrams of prednisone each day, the highest dose. You can read that a “high” dose of the drug starts at 40 MG a day.

It gave me a surge of energy, fitful sleep, and it did knock back the symptoms. I’ll have a follow-up MRI on Thursday on my cervical spine — the one area we didn’t check last month — that I assume will show a new lesion causing all this ruckus.

My hope is that the worst is over, even if again my worst is not nearly as bad as the worst for others with my condition, but the reality also is that I probably won’t feel “normal” for months (and that normal is a constantly moving target for all of us, particularly when you have a chronic condition).

Starting the course of steroids at basically the exact moment we were “celebrating” the five-year anniversary of the COVID shutdown in the United States was not lost on me.

I had already been wrestling with that milestone, what to make of it, avoiding some of the coverage (as I think others are doing) while also trying to reflect on what it all means.

My personal MS timeline and our collective COVID timeline are far different things, but they are unified in many ways.

Most aptly this:

The things I had worked so hard to forget, I suddenly had no choice but to remember.

In both cases, there was a clear but confusing start. And then a need to push through. There is no real defined end, even if there are milestones. Plus the bargaining, the straining to somehow find positives, the remembering of not so much the past but a version of a revisionist history.

Was it that bad?

What was it like?

With the relapse, the challenges have been both mental and physical. It brought to the forefront a disease that for many years, for most of the time, I have been able to compartmentalize and let run in the background as I lived my life. I have things I need to manage, but mostly they have been mild and routine.

Having familiar and more aggressive symptoms makes you aware of your body in a way that makes it hard to think about other things. Constantly thinking about whether you are going to feel well or not, evaluating your state in the moment, can make you anxious. Anxiety causes stress, which can make your symptoms worse. And then when your symptoms get worse, you get more anxious.

That was a familiar cycle, one that I had tried to forget and largely did until it all came back to me.

My mentality and the way I was wired 11 years ago, and now, and through COVID, is largely this: Push through it. Don’t let it get the best of you. Come out on the other side.

That other side, though, is elusive. With COVID, the goalposts were always changing. Weeks became months, months became at least a year, and the way it “ended” (if it ever really did) was more personal than collective.

For me, strangely, COVID changed when I got it for the first time in August 2022, about 2.5 years after the first lockdown started. Having it and getting through it was not fun, but by then I had received multiple doses of the vaccine. It was a really bad virus that knocked me down for the better part of a week. After that, I felt like I knew what to expect and didn’t have the same level of fear.

How COVID affected my life and the lives of everyone around me, though, is still a puzzle to untangle. One of the few things I have read on the five-year anniversary, this excellent New York Times piece, puts that into perspective.

I have at times found myself frustrated by what we didn’t know at the start and how we might have done things differently if we did. But it is hard to relive those days — they started for me with a 5-year-old, a 3-year-old, a newborn and my wife just back from maternity leave all packed into a small house — and remember just what they were like.

We took walks that I romanticize, remembering our 3-year-old’s obsession with a plastic spider outside a neighbor’s house and thinking about our kids scampering on a low brick retaining wall that was certainly more dangerous than any of the closed outdoor playgrounds.

We were in it together, doing it for a reason, and it mattered. But it was hard. No, check that: Mostly it just really sucked. Death was real and horrifying. Nothing felt save or natural. We were limited. Our mental health suffered. Our lives were put on hold and rerouted.

We made it through, and a lot of other people had it much worse, but why would we want to remember any of it now?

The “other side” of an MS relapse or even the disease in general is even more complex. It does not go away, even if it often fades for a while.

At a certain point, it shifts from having the potential to bring more dramatic swings (the “relapsing-remitting” phase that I am in and probably will be in for a while longer) to a considerably slower trajectory (the “secondary progressive” phase) during which existing symptoms can get worse over time.

The stability of my disease course has given me optimism over the past decade that I can manage to still live a long and relatively healthy life, and I still believe that.

But now I remember that I am hardly invincible and definitely not immune from its effects.

I am having to manage my energy and days in ways that I haven’t had to consider in quite a while. I am asking myself annoying questions, seeking internal assurances, things like, “If you had to feel like you do today for the rest of your life, would that be OK?” Usually in the last couple of weeks I could answer “yes,” but I am also pretty stubborn.

But yes, usually stubbornly positive. I’ve been trying to ground myself in gratitude for the good moments instead of wallowing in the tough ones, and in that way I have been able to reframe this frustration over suddenly having to remember what this all feels like.

I’ve been through it before. I’ve recovered. It’s not new, so it’s not as frightening as when I was feeling lousy before even being diagnosed. And more than that, I know things that help me feel better.

Rest helps. Calm breathing, meditation and other de-stressing techniques help. Exercise helps. Healthy eating helps. Good sleep habits help. Staying present helps.

The overachiever in me is already doubling-down on those things, and part of me is disappointed in myself that I had become lax or about some of them and taken things for granted in the months or even years leading up to this flare-up.

It’s human nature, but I needed a reminder: You need to do the things that make you feel good in order to stay feeling good.

I’m more apt to ask for help now. I even modified my work schedule last week and took a stressful assignment off my plate, something obvious for most people but something my wife knows was a massive step for me.

I’m better equipped to handle things now. But none of that offers a guarantee. As someone who has always been most comfortable with order and clarity in his life, that lack of certainty is the hardest part of MS just as it was the hardest part of getting through the pandemic.

On Friday, the last day of the steroid dose, I woke up (again) at 4:30 a.m. because that’s what 1,250 MG of prednisone will do.

I laid in bed until 6 a.m. and then got up, made myself a large breakfast and ate it while taking 25 pills.

Somewhat impulsively the day before, my wife and I had managed to find a last-minute babysitter for Friday night so we could go out to a jazz club to see a group my dad and I had seen several years prior.

I wasn’t sure it was the right decision in the moment, but Friday was a good day. I was a little nervous about how I would feel Saturday without the drugs (update: mostly decent, and hopefully the parts that aren’t will be cured by a good night of sleep that has been elusive in the past week). I wasn’t sure the drive into downtown Minneapolis was a good idea given how it was set to coincide with the arrival of odd mid-March thunderstorms.

But we went. We found parking and absorbed ourselves into the North Loop neighborhood that I lived in nearly 25 years ago when my wife and I first met.

The club was unfamiliar, just as a lot of the surroundings now are, but not everything needs to stay the same.

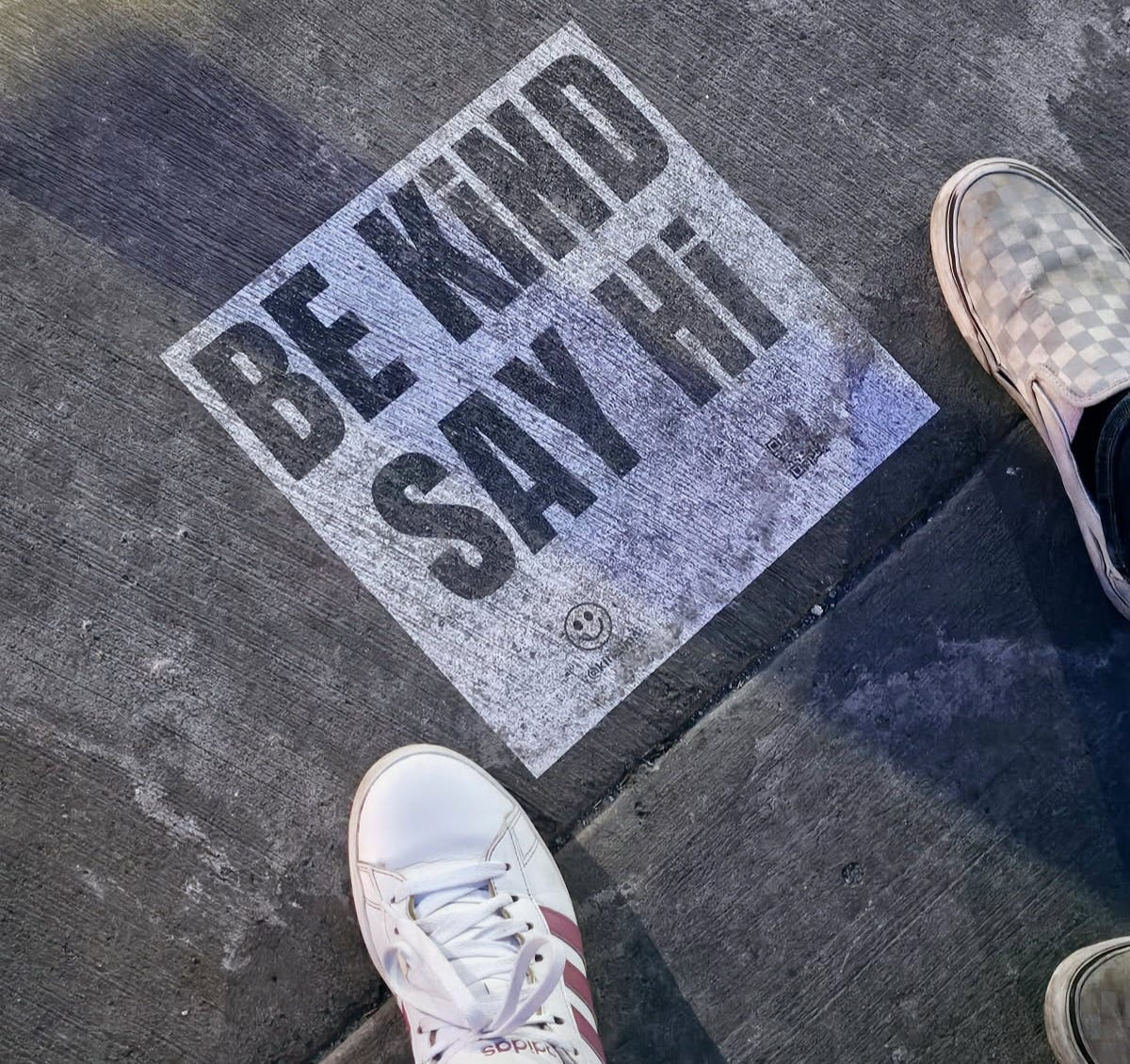

She snapped that picture you see at the top of this post, and then we wandered into the bar and managed to snag the last two seats available.

We talked about things other my health and our kids, we had a few big laughs and we listened to the music. Then we ran to the car just before the rain fell hard and drove home through a downpour and lightning to our three night owl children.

It would have been far easier to not go, and maybe even smarter, but sometimes the easiest way to get out of the trap of the past and future is to be in the moment.

Just because you try to forget something doesn’t mean it never happened. Just because you can’t imagine it doesn’t mean it never will.

All of it just means you’re alive right now.

Something I got away from at the start of 2025 but is also front-brain now: Proceeds from any new paid subscribers between now and the end of March will benefit the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. I donated hundreds of dollars in 2024, in part with your help, and I plan to make another donation in a few weeks.

It sounds like you've been through the wringer with the recurrence of the major MS attack, and we're all glad that you feel better. Hopefully, your health will continue to stabilize. Even though you recognize the relative complacency to which you'd become accustomed before this flare-up, your self-reflection allows you to live more in the present and do what you need to do to maximize good health, so you can see clearly the beauty that surrounds you. Appreciation for what we have should be the perspective of more people, a view that would more greatly respect the positive elements of life.